“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

―George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman

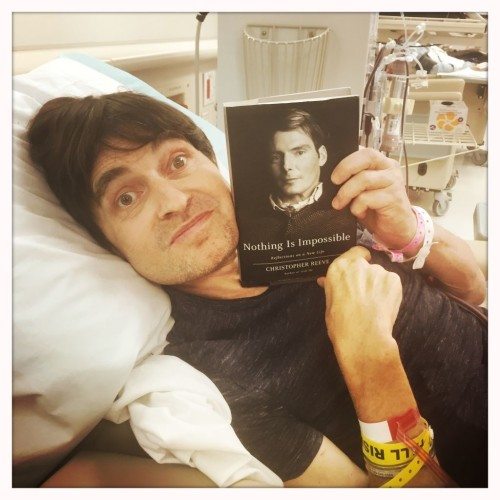

Some time ago, I’d found Christopher Reeve’s biography, “Nothing Is Impossible,” on the shelves of the care home. I’d started reading it, but didn’t get far before it disappeared into the book pile of good-intentions by my bedside. I never know what will keep his interest, so I often take a couple books at a time with me to dialysis, just in case. This one came in the bag today.

I started reading cautiously, worried that he might react negatively to someone writing so frankly about his disabilities. The book was published 7 years after Reeve’s catastrophic accident, and he’d used the time to work through the battlefield of his mind and come out with a strong attitude about life in general. Vernon loves to be read to—on good days. But this was no Narnian landscape of vibrant fantasy, this was someone talking about life in a wheelchair—someone who had a family he loved, friends he admired, passion and purpose, but he couldn’t move his body on his own. He was also someone who admitted depression and grief were part of the journey. He spoke of his post-accident life as his “new life.”

Here is an excerpt:

“The emotional extremes of adjusting to a catastrophic illness of disability range from suicidal despair to recovering an appetite for life. Somewhere in between ins a gray area of numbness. You don’t feel really depressed but you don’t get excited about anything either. One day blends into another as the same rituals of care are repeated over and over again. You think about calling a friend but decide not to because there’s not much to say. Often you have to be persuaded to go outdoors by a nurse or a family member who reminds you that you’ve even sitting in your office without moving for more than six hours.”

I looked up at Vernon. Too much? What do you think? He almost smiled: “This is amazing. Keep reading.” Of course he says that whenever we read something he likes, but I was surprised he liked this so much. He even asked if he could have a go at reading himself. I think we both got a buzz over the idea for a minute, but his reading eyes are no good so he handed it back. (But I promised him I’d look for some books on cd so he can get stories read to him in his room.)

Since he liked the book so much, I asked if he’d pose with it.

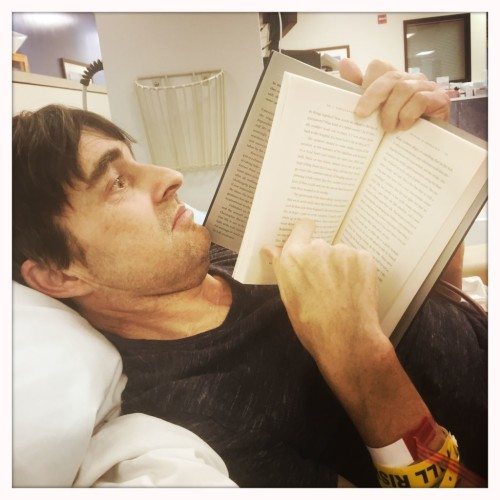

“Don’t you want to take one of me reading?” he asked.

Here is another part he seemed to respond to (perhaps it was my imagination):

“And then, in an instant, the moment my head hit the hard ground…everything changed. Or so I believed. As I lay in bed in the ICU, I concluded that I could no longer be a real father to my three children. I assumed that my new life as a quadriplegic would not only mark the end of the life we had known, but cause enormous psychological and emotional damage to them as well. How could I relate to them if we couldn’t do things together? How would we adjust to the loss of spontaneity? What kind of a father would I be if I literally couldn’t reach out to them, if I was always going back to the hospital, if a nurse had to be on duty 24/7?”

He continues: “Now I gave them my full attention, and I soon learned to listen more than talk. That began a process of discovering that, in bringing up children and relating to others, sometimes being is more important that doing. I was also to learn that even if you can’t move, you can have a powerful effect with what you say.”

I think Vernon and both were encouraged by the words of this book today.

61

I can understand why you may feel this was not a “perfect” read for Vern … but who knows maybe it is what he needs right now .. Vern has always been a thinker ..and always tried to maneuver round situations from many angles ..maybe his brain is moving round this situation???

please let me know what talking books he may like … guess they come on cd?? will they work in the US if i send some??

xx have a great EASTER WEEKEND xx love to you all xx

Allison,

It is good that Vern liked Christoper Reeves’ book about “Nothing Is Impossible”. Have never read the book but if Vern like it there was something there that got to him. To me it is good to see him liking something about someone in many ways in a condition as Vern. And with God nothing is impossible also.

Have a happy and nice Easter.

Love,

Becky